Hang Seng Bank was located at 163-165 Queen’s Road Central, in a white five-storey Western-style building with aluminium windows and an elevator. The tall modern building stood out from the three- and four-storey pre-war Chinese tenement houses in the neighbourhood. Shops selling garments, leather goods, pharmaceuticals, watches and clocks, jewellery and stationery lined the street, alongside several noisy Chinese restaurants and Hong Kong style cafes. A number of Chinese-owned banks, including Kwong On, Dao Heng, Wing Hang and Wing Lung, were also in the vicinity.

Inside the banking hall, some twenty employees were busy talking to customers or doing calculations behind the counters under a flood of white fluorescent light. The steady clatters of the abacuses mixed with the rhythmic churning of modern calculating machines. This meeting of East and West was also reflected in how the staff dressed: some wore ties and dark grey or blue Western suits, while others wore loose-fitting grey Chinese suits with high stiff collars. This mingling of different periods and cultures permeated the entire bank all the way up to the senior management.

Hang Seng first opened for business in Hong Kong on 3 March 1933 and the firm’s original founders were Ho Sin Hang, Lam Bing Yim and Sheng Tsun Lin who both had businesses in Shanghai, and Leung Chick Wei who, like Ho, started his own business in Guangzhou. Each was a successful financier in his own right during the 1920s, but civil war and the threat of Japanese invasion in the early 1930s forced them to leave the Mainland in the hope of finding a safe haven in Hong Kong. The British colony was then politically stable and allowed private businesses to operate on a laissez-faire basis with minimal restrictions, an advantage which was not lost on the founders. After arriving in Hong Kong, Ho, Lam, Sheng and Leung came to know each other through their gold trading and soon became friends and business partners.

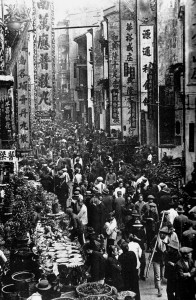

Hang Seng started business as a yinhao at 70 Wing Lok Street, a narrow street in the Sheung Wan area lined with traditional Chinese tenements and bustling with the business activities of bankers, traders and retailers of all description. Lam was the chairman, Ho the general manager and Leung his deputy. About 11 staff crammed into the bank’s 800 square foot premises. There was so little space that a customer had to take only three steps from the entrance to the bank counter. The four characters of the bank’s name – Hang Seng Yin Hao – were boldly written in black on a large wooden panel hanging across the front of the building, and on the two pillars supporting the upper floor balcony on each side were smaller Chinese characters describing the bank’s services: remittances, exchange and gold trading. The Chinese Gold and Silver Exchange Society, the focal point of local Chinese banking activities, was nearby in Masa Street.

In the tradition of its founders, Hang Seng quickly became an active gold trader, but it also expanded into the lucrative remittance and currency exchange business between Hong Kong and the Mainland. Like other yinhao, it provided these services to Chinese traders in textiles, pharmaceuticals, rice and dried sea products, and performed a role that foreign international banks were reluctant to play. Foreign banks at that time transacted primarily with foreign companies, and dealt with the Chinese community only through their compradors – English speaking Chinese who would guarantee the banks’ loans to the yinhao and handle all local Chinese business.

Hang Seng was started up as a precaution against war, but paradoxically the company made its first major fortune from the start of the war. When the Japanese invaded China in 1937, everyone who could afford it rushed to buy and hoard gold, and a flurry of remittances came to Hong Kong from Shanghai, Hankou, Guangzhou and other major cities in China all looking for a safe haven. Hang Seng benefited handsomely from these activities. Thanks to the partners’ business connections on the Mainland, the bank also secured an active role exchanging Yuan for foreign currencies on behalf of the Nationalist government, which needed foreign exchange to finance its war against Japan. According to Ho Tim, Yuan banknotes used to arrive in Hong Kong by the truckloads, and the profits to be made were enormous.

After the Japanese occupied Hong Kong in December 1941, the founding partners and their staff sought refuge in Macao and continued to trade gold in a small office under the name of Wing Wah Yinhao. They moved back to Hong Kong after the war ended in 1945, and re-started Hang Seng’s operations at 181 Queen’s Road Central, which were larger premises that the bank had purchased before the war.

Q.W. Lee, who had worked with some of the founders in Macao, joined Hang Seng the following year. After leaving his native village of Kaiping for Hong Kong at a young age, Lee attended St. Joseph College, a Catholic English secondary school. He left school a year before he was due to graduate in order to support his family and joined China State Bank as a trainee. With his knowledge of English and commercial banking, Lee was assigned the specific task of dealing with foreign gold traders and soon became an indispensable member of the management team.

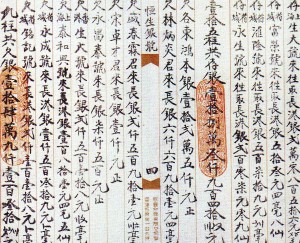

The intensification of the civil war between the Nationalist government and the Communists again brought the bank great opportunities for trading gold. China’s economy was still recovering from the devastations of war and the Nationalist government needed to raise funds to fight the Communists. Inflation skyrocketed and to stabilize the currency the government instituted the Gold Yuan in 1948, valued at four Gold Yuan to one US Dollar. All Chinese National Currency (CNC) previously in circulation in the market had to be turned over to the government at an exchange value of one Gold Yuan to three million CNC. By 1949, the Central Bank of China was issuing bank notes in denominations of one hundred thousand Gold Yuan for everyday use. Completely losing faith in the national currency and the Nationalist government’s ability to control inflation, many businesses and individuals resorted to holding gold, against regulations. Some tried to speculate in the Hong Kong gold market through the yinhao. With its founders’ business connections and trading expertise, Hang Seng executed many of these transactions and quickly became the doyen of the Hong Kong gold market, so practically all gold traders had to follow its lead. Ho won recognition as the authority behind Hang Seng’s success and was elected as chairman of the Chinese Gold and Silver Exchange Society, serving from 1946 to 1949.

At the height of the firm’s success, however, historical events again intervened and forced Hang Seng to take a new course. When the Korean War started in 1950, the United Nations imposed an embargo on all trade with the PRC; all gold trading, currency exchange and remittances involving the Mainland came to a halt, and the bank lost the mainstay of its business overnight. The founders realized that the business must adjust to the new political situation.

Ho, who became the group’s new leader after Lam Bing Yim passed away in 1949, was acutely aware that times were changing for the yinhao and wanted to explore the alternatives. Between 1950 and 1952, Ho toured the US, Canada, Southeast Asia, South Africa and Europe, and visited banks and financial institutions in seventeen cities (including New York, Los Angeles, Havana, Lima, Tokyo, London and Paris) in search of new ideas and business opportunities. Q.W. Lee accompanied Ho and his wife on these tours and acted as Ho’s personal secretary and interpreter. At the end of his tour, Ho decided that Hang Seng should still concentrate its business in Hong Kong but would have to become an international commercial bank.

Ho, who became the group’s new leader after Lam Bing Yim passed away in 1949, was acutely aware that times were changing for the yinhao and wanted to explore the alternatives. Between 1950 and 1952, Ho toured the US, Canada, Southeast Asia, South Africa and Europe, and visited banks and financial institutions in seventeen cities (including New York, Los Angeles, Havana, Lima, Tokyo, London and Paris) in search of new ideas and business opportunities. Q.W. Lee accompanied Ho and his wife on these tours and acted as Ho’s personal secretary and interpreter. At the end of his tour, Ho decided that Hang Seng should still concentrate its business in Hong Kong but would have to become an international commercial bank.

On 5 December 1952, Hang Seng was incorporated as a limited-liability company. Ho Sin Hang was elected chairman of the board with Leung Chick Wei as vice chairman, and Ho Tim was appointed general manager. After its incorporation, Hang Seng upgraded itself from a yinhao speculating in gold and currencies to a full-fledged commercial bank that could finance international trade, take deposits from the general public and make loans. The change was timely. Mainland industrialists sought a safe haven in Hong Kong after the communist takeover, over a million refugees fled to the colony, and the conditions were ripe for the manufacturing industry to take off. As factories sprang up throughout Hong Kong the demand for financing soared.

International banks such as The Hongkong and Shanghai Bank (later known as Hongkong Bank, and now HSBC) and Chartered Bank (now Standard Chartered Bank) abandoned their comprador system and started to deal directly with the larger and better-known Shanghainese textile groups such as Windsor, South Sea, Nanyang and Nan Fung. Hang Seng, on the other hand, mainly took care of smaller businesses within the Guangdong community, including the manufacturers of garments, toys, plastics, metal products and electronics that would later spearhead Hong Kong’s economic growth. As most of these small businesses did not have a proper balance sheet and could offer little financial data to support their loan requests, many of the bank’s initial loans were based on personal relationships and trust. Many of these small businesses later grew into large corporations and formed the backbone of the bank’s corporate customer base. In the late 1960s, real estate developers also became clients and start-up firms such as Sun Hung Kai, New World and Henderson remained loyal customers of the bank when they later became major corporations.

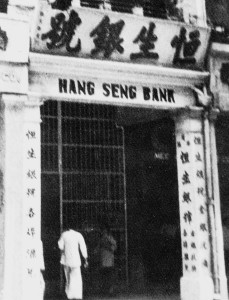

With an expanding business, Hang Seng soon outgrew its second location at 181 Queen’s Road Central and in 1953 it moved down the road to numbers 163-165, a five-storey building. The new headquarters prominently displayed the bank’s name in English – “Hang Seng Bank Ltd.” – across the main entrance. Hong Kong’s Chinese financial district as a whole had shifted east from Wing Lok Street, moving closer to the Central District as commercial banks and Westernized enterprises replaced yinhao and traditional Chinese shops. Compared to Wing Lok Street, this part of Queen’s Road Central was wider, with more traffic and a number of new multi-storey buildings on either side of the road. In 1960, the bank went public and officially changed its Chinese name from Hang Seng Yin Hao to Hang Seng Yin Hang (“Hang Seng Bank”). The change in that last character was the milestone marking the company’s re-birth as a modern commercial bank.

When Hang Seng celebrated its 30th anniversary on Christmas Eve 1962, it also celebrated yet another move, to a brand new building facing the harbour at 77 Des Voeux Road Central. The new building, twenty-two storeys high with a steel frame, aluminium trimming, and grey and green glass curtain walls, was the tallest and most modern in Hong Kong at the time and a fitting symbol of the bank’s successful transition to modern banking. By this time, Hang Seng had total assets of HK$355 million and a staff of 400, making it the largest Chinese-owned commercial bank in Hong Kong. Echoing Confucius, Chairman Ho said at the celebrations: “At thirty, we stand on our own feet.”

Stanley Kwan, with the former and current Hang Seng Bank Building in the background, in Central, Hong Kong, 2009

Source: The Dragon and the Crown: Hong Kong Memoirs, by Stanley Kwan with Nicole Kwan, Hong Kong University Press, 2009, 2011